Field Notes: Philip Johnson’s Glass House

Glass, brick and a complex past in New Canaan, Connecticut.

New York City is the greatest, most maddening place in the world. But even the most ardent city lover needs an escape. Sometimes you crave stillness that isn’t just a momentary subway delay or a 3 a.m. lull in street noise. And while vacations to far away places, like Tokyo, Tangier, or wherever Instagram tells you to go next, may dazzle you while away from the city, there’s something particularly grounding about going somewhere nearby. Places like New Canaan, Beacon, Cold Spring, Hudson, these aren’t escapes from New York, in my opinion they’re extensions of it. They add dimension to the story. They remind you that the city’s cultural, architectural, and artistic history doesn’t stop at its borders. It ripples outward. Consider it a breath of fresh air, one that is not a plane ride away, but rather just a Metro-North train ride from Grand Central.

Compared to New York City, it’s strange how quiet it is in New Canaan. Swapping the constant buzz of the city for the delicate stillness of Connecticut suburbia feels like passing through a membrane. And if you’ve come here, as I did, with the Glass House in mind, it feels fitting. You’re taking part in a kind of quiet rite, an journey for anyone drawn to beauty, space, and meaning. One made by many artists, architects, and dreamers alike.

Getting There

The Glass House is open seasonally from mid-April through mid-December. Today, April 17th, being the first day of the tour season for 2025. Getting there is fairly easy from the city. A 90-minute ride on the New Haven Line from Grand Central to New Canaan Station. From there, it’s a five-minute walk to the Visitor Center, where tours begin, typically lasting about two hours. The property is only accessible by guided tour (self guided tours take place only on Sunday, though I would not recommend unless you are a returning visitor). Book in advance, they fill up fast. The Glass House team handles transportation from the centre to the site itself via shuttle. If you’re driving from New York City it’s about an hour to an hour and 45 minutes depending on where you begin your journey, of course.

The surrounding town is also worth a visit, filled with charming shops and a couple places to grab a coffee. I would also add Grace Farms, another beloved New Canaan spot, but I think squeezing both into the same day would be a disservice to each.

The History

Philip Johnson was one of the most influential and polarizing figures in American architecture. Known for his striking modernist designs and later, his dramatic postmodern turns, Johnson had a flair for the theatrical. Educated at Harvard and a founding curator of MoMA’s architecture department, he shaped buildings but also public taste.

Johnson purchased the plot in New Canaan in 1945, shortly after finishing his architecture studies at Harvard. At the time, New Canaan was quietly and slowly becoming a hotbed of modernist experimentation, thanks to the “Harvard Five,” a group of Johnson’s colleagues and professors who settled there, Marcel Breuer, Landis Gores, John Johansen and Eliot Noyes. These were architects hoping to challenge the traditional American architectural approach. New Canaan’s wealthy and progressive clientele and abundance of land made it the perfect testing ground.

Johnson chose this site specifically because of its gentle slope, old stone walls, and iconic natural backdrop all of which would sharply contrast the minimal, and groundbreaking transparency he was envisioning. Construction on the Glass House began in 1948 and was completed in 1949, a remarkably fast process for such an iconic building.

Johnson always called Mies van der Rohe his hero and then, quietly, his rival. The Glass House was clearly inspired by Mies’s Farnsworth House in Illinois, which was designed earlier but constructed later. Johnson had access to Mies’s plans while working at MoMA, and there’s a long-held theory that he fast-tracked construction on the Glass House so he could publicly claim the concept first. The similarities between the two homes are unmistakable.

The House

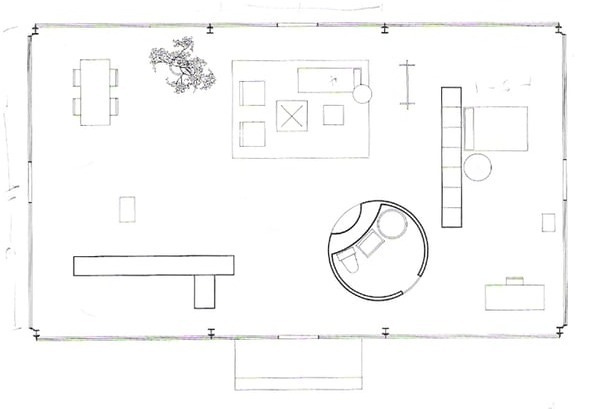

The Glass House is one large room enclosed in floor-to-ceiling glass on all four sides, framed in black steel. There are no hallways, no rooms, no partitions. The only privacy you can get in the space is in the cylindrical brick structure in the centre that contains the bathroom. The same brick extends to house the fireplace, the only true “mass” in the space.

The layout is deliberate, a sleeping area, dining area, kitchen, and living space flow seamlessly into each other. There’s no hiding here, not from your guests, the landscape or yourself. The furniture sits low and harmonious with the space. The view is the artwork. During our tour, I recall the guide quoting Johnson, telling us how he would brag that he had the most expensive wallpaper in the world.

And then there are the two ladies, formed in bronze, standing side-by-side within the Glass House. Our tour guide told us the work by Elie Nadelman, was placed by Johnson with clear intent. He wanted the house to feel inhabited and watched over. A twin version of this sculpture resides at the David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Center where the figures gaze out over the lobby, watching ballet-goers with the same serene gaze. It’s one of Johnson’s subtle through-lines, tying together his private world in New Canaan and his public architectural one in New York City.

The Glass House’s most immediate companion is the Brick House, built at the same time but entirely different in material and intent. Where the Glass House is transparent, open, and performative, the Brick House is opaque, enclosed, and private. Johnson often described them as yin and yang, two parts of a whole. One for showing, one for retreating, one for spectacle, one for sleep. They were constructed together, with the Brick House initially used as a guest space and for more traditional private functions.

The Evolution

Over the decades they lived there, Johnson and his partner David Whitney turned the estate into a full compound. 14 structures across 49 acres. The Painting Gallery, built in 1965, is kind of like a modernist tomb designed to house works by Frank Stella, Julian Schnabel, Cindy Sherman, among others on its rotating walls. The Sculpture Gallery came in 1970, filled with platforms at different heights, skylights, and angular shadows. There’s the Ghost House, the Library, and the pavilion near the entrance, a much later addition.

David Whitney, Johnson’s partner of 45 years, was a curator and art world darling in his own right. Their relationship began when Johnson was a professor and Whitney was a student. Obviously, a dynamic that like much of Johnson’s legacy, invites scrutiny. As with much of Johnson’s life, the power dynamics are complicated but still worth mentioning. Whitney was 22 years old when they met, while Johnson was in his 50s and had considerable institutional clout.

Whitney played a major role in shaping the Glass House compound. He filled the galleries, hosted the artists, cultivated the vision. In many ways, the Glass House is as much his as it is Johnson’s.

The Reflection

To visit the Glass House is to step into an ongoing conversation between architecture and landscape, between power and deceit, between legacy and shame. It’s impossibly beautiful but it’s also hard to ignore the contradictions. Johnson’s history is complicated, to say the least. An early and disturbing fascination with fascism in the 1930s, his later erasure of that chapter, a tendency toward elitism, the rumours of his abuse of institutional privilege both professionally and personally, and a complicated dance between being a tastemaker and a follower of others' genius. It’s important and necessary to appreciate the architecture while acknowledging the man’s contradictions.

These contradictions live in the walls, or I guess I should say they would, if there were any. Now his actions lay bare just like his old home, undeniably transparent for the world to see.

Back in New York, Johnson left his mark around the city. He designed the David H. Koch Theater at Lincoln Centre (a personal favourite of mine), co-designed the Seagram Building with Mies, and gave us the AT&T Building, sitting at 550 Madison Ave, a defining symbol of postmodern architecture. His work straddles seriousness and spectacle, always dramatic like its creator but also in a way, aware of it.

The End

Philip Johnson lived in the Glass House until his death in 2005. David Whitney died just a few months later. Before they passed, the couple made it clear that the property should be preserved but not as a static architectural monument, but as a real lived-in, breathing artwork. A place people could continue to visit, wander through, and think inside of.

They left the Glass House under the care of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which now maintains the site meticulously. Everything you see today, from the arrangement of the Barcelona chairs to the artwork in the Painting Gallery to the books on the shelves, is presented exactly as it was during Johnson and Whitney’s lifetime. It's less like walking into a museum and more like stepping into someone's mind, paused in time.

And that’s the real magic of the Glass House. It's not just something to look at, it's a place for looking, of all kinds. Looking outward, across the open green. Looking inward, at the architecture of taste and influence. Looking back, at the questionable legacy of a man who shaped the cultural landscape of architecture in the twentieth century.

The Future

The Brick House, which had been closed to the public for years due to water damage, reopened in late 2023 after an extensive renovation. The process involved structural fixes and deep historical restoration. Reupholstering original fabrics, studying old photographs, even reverse-engineering furniture. The result is hauntingly beautiful. Kind of like a time capsule but not, it’s a preservation of a unique nature.

The Glass House has hosted its share of legends: Andy Warhol, Frank Stella, David Hockney, even Peggy Guggenheim. More recently, it’s become a kind of modernist hotspot for the stylish and design curious ‘it girls’. Solange recently visited and posed for an editorial in the Glass House, Sculpture Gallery and Brick House for Document Journal. Solange actually joins Andy Warhol as the only two guests in history to be photographed in the bedroom of the 1949 Brick House. Kendall Jenner also recently dropped by during Fashion Week. So, if you want to witness this deep history and add your name to that exclusive list of visitors, make the journey to New Canaan as many have before you.

This was a delight to read, learned so much!